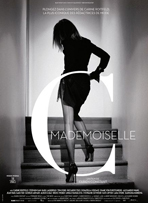

The Night Porter

“Maybe one day I'll become a film star. I'd love to become a film star... What do you think? A remake of The Night Porter with me instead of Charlotte Rampling?”

— Carine Roitfeld to Talk Magazine, April 2001

I came across the above quote recently and had to laugh. How very Carine — not for her the sophomoric Fifty Shades of Grey! If she were to do a film, she would naturally gravitate towards what is arguably the most controversial S&M narrative ever made.

The Night Porter, directed in 1974 by the Italian Liliana Cavani, stars Dirk Bogarde as Maxmilian Theo Aldorfer, a former Nazi SS officer, and Charlotte Rampling as Lucia Atherton, a survivor of his concentration camp. Flashbacks show Max tormenting Lucia, but also acting as her protector. The two are reunited 13 years after World War II, in a Vienna hotel where Max is now a night porter. There they fall back into their sadomasochistic relationship and all hell breaks loose.

It is a deeply disturbing film. The first time I sat down to watch it years ago, I couldn’t make it all the way through. But I decided to give it another try, taking a more detached view and trying to analyze what, aside from the obvious attraction of the taboo, would appeal to a woman as intelligent as Carine Roitfeld.

What struck me the most about The Night Porter this time around was the symbolic use of light and dark in the film. Max is both literally and figuratively a dark character. He has a slick, shadowy handsomeness, beneath which roils deep perversity. He works at night for a reason. He needs the cover of darkness for the sick ministrations he performs to the hotel guests — with needles, pills, or flesh. It turns out that the twisted things he does in the unlit rooms provide an outlet for the cruelty that he was able to give full reign to in his former life as an SS officer.

Enter Lucia, a conventional bourgeois housewife, dressed in blacks, greys, and slate blues, her hair tidily pinned up with nary a strand out of place. A flashback shows the contrast between her present-day appearance and her previous association with Max. We are shown Lucia as Max first saw her: one in a line of prisoners being checked into his camp, she stands nude, her bobbed hair bound by a ribbon, clothed only in white bobby socks and black Mary Janes. Max singles her out from all the other inmates and trains a camera on her, flooding her with light from its blub. The light makes her a brilliant, over-exposed white. This vision highlights the symbolism of her name: Lucia, a pun on “light” and St. Lucy, the patron saint of the blind.

Thus Max’s statement that he works at night because he has a sense of shame in the light has a double meaning. He feels shame for what he has done, but can’t overcome his compulsion to continually repeat the past — his hotels “guests” replacing his concentration camp victims. But he means it metaphorically as well in relation to Lucia, “the light one,” whom he deeply loves, albeit in a deeply twisted way.

Lucia’s association with light continues once she is reunited with Max. From that point on, she is never in dark clothing again. She initially struggles against him in a flowing, icy-white nightgown. Later she revels as a willing captive in his apartment dressed in a thick, cream-colored fisherman’s sweater over filmy white lingerie shorts. And her hair is never up again, but released... the flowing, tousled, sexy mess of the renegade. By the time Lucia states, “Max is more than just the past,” we have guessed this already from her transformation.

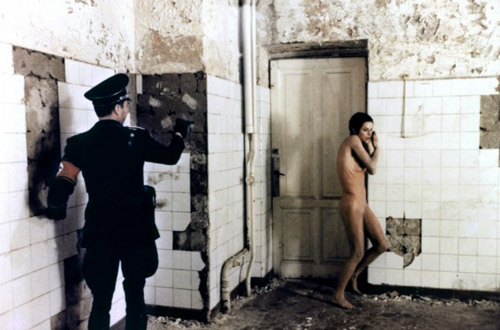

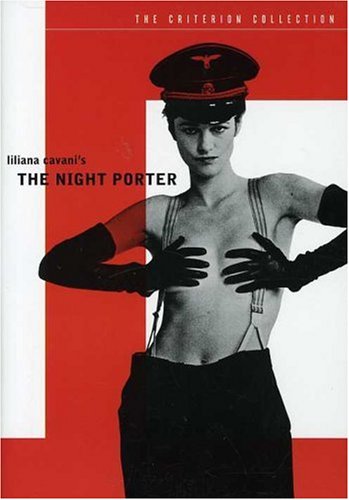

One cannot speak of the visuals of The Night Porter without addressing the iconic scene in which Lucia sings a Dietrich standard to the Nazi officers. It is a scene Carine herself might have styled: in a large, barren, white-tiled room, a number of SS officers lounge in bored disinterest while Lucia sings to them with clear relish and intent to titillate. She is nude from the waist up, wearing a few choice accessories. An officer’s cap is pulled low over her brooding eyes. Above-the-elbow black leather gloves encase her willowy arms. Striped suspenders create a graphic of two stark lines framing her bare breasts. Finally, there is a set of men’s black pinstriped trousers, the front of which she intermittently grinds and massages throughout the song. The perversity of the scene reaches its zenith when Max, who has been watching her with a crazed gleam in his eye, rewards her at the end of her performance with the severed head of a fellow prisoner who had been bullying the other inmates. Later he proudly recounts the scene to a friend, exclaiming, “It was biblical!”

It is worth pausing to consider the importance of Max’s allusion to the story of Salome. Is he, in aligning himself with the ancient biblical tale, trying to exonerate himself? He describes what should have been a derogatory episode for Lucia as one that was instead a triumph for her; like Salome, she wields great power.

It is this idea of a woman who is captive but not a victim that brings Carine Roitfeld to mind the most. Carine has defended her taste for showing bondage in her photos: “I don’t want to portray women as victims of male desire, to make them sex objects or first-degree objects of desire... when I’ve shown a woman tied up like one of Araki’s models, she’s always chic and doesn’t look as if she’s suffering — and this makes her stronger I think.” (Irreverent, 210) In the burlesque scene, Rampling’s Lucia is definitely chic and certainly not suffering. This aura is repeated later, when she is bound in chains in Max’s apartment. There is nothing weak about her when she rebuffs her would-be rescuers with a calm but steely, “I’m here of my own free will.”

The role of dark and light is perhaps most poignant in the closing scene of the movie. Max and Lucia attempt an escape from the neo-Nazi cell that has surrounded Max’s apartment, determined to separate them. Holding hands they run, dressed in the costumes of the past they could not and would not let go: he in his SS uniform, and she in her white little-girl’s dress and knee socks. But their pursuers execute them, midway across a bridge, at dawn. The lighting of these final moments is amazing. I don’t think it’s any accident how literally the director illustrates the darkness being chased away by the light.

Twisted and sensational though it is, there’s no denying how artful The Night Porter is in dealing with themes of sexual transgression... Like so many photos styled by Carine Roitfeld.

The Night Porter stills © 2012 Criterion. Carine Roitfeld photo © 2011 V Magazine, LLC. S&M modification by Kellina de Boer.

Carine Roitfeld | in

Carine Roitfeld | in  Favorites,

Favorites,  Films

Films

Reader Comments (2)

;-)